Read more

Designing Sep Licensing Negotiation Groups to Reduce Patent Holdout in 5g/IoT Markets

In response to concerns that inefficiencies in SEP licensing may have a negative systemic impact on the development of emerging 5G and IoT Markets, the European Commission (EC) convened an Expert Group on Licensing...

The OECD Global Forum on Competition 2022 took place in Paris on 1-2 December, gathering officials from around 100 competition authorities. Its four main sessions focused respectively on (i) the goals of competition policy, (ii) subsidies, competition, and trade, (iii) interactions between competition authorities and sector regulators, and (iv) remedies and commitments in abuse cases. Dr Anna Renata Pisarkiewicz (Research Fellow at the Centre for a Digital Society) has written the Background Note for the OECD Secretariat for the last session. This post reflects some of the main issues that have been discussed.

Remedies versus commitments in abuse cases

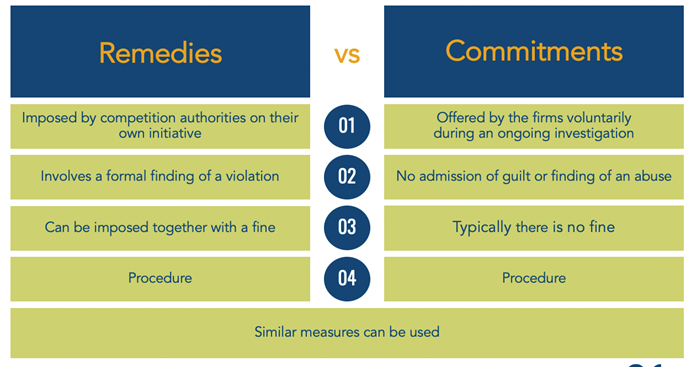

As explained in the Background Note, the distinction between the term ‘remedy’ and ‘commitment’ originates from the wording of EU legislation. Commitments are governed by Article 9 of Regulation 1/2003, whereas remedies by Article 7. The overview of national laws and the discussion that took place during the Forum has made it clear that terms used in individual jurisdictions vary. Also, while the most cited reason that drives the use of commitments is procedural economy, ultimately different considerations might drive national preferences for the use of one tool over the other, raising a different set of challenges.

Concerning terminology, in very simple terms:

- Commitments refer to measures that firms offer voluntarily during an ongoing investigation and that are formalised in a decision that involves no admission of guilt or formal finding of abuse;

- Remedies refer to measures that competition agencies can impose on their own initiative when they consider them to be necessary to bring the infringement to an end and that are formalised in a prohibition decision that includes the finding of a violation.

While the form or content of remedies and commitments may be similar, the applicable procedures differ.

The trend in the use of commitments in abuse cases

The number of competition authorities with the power to accept commitments has been growing steadily over the years. This means that today the academic community can engage in a very interesting research exercise: it can compare approaches and experiences of the countries with a long track record in using commitments with countries that have introduced commitments into their national laws only recently.

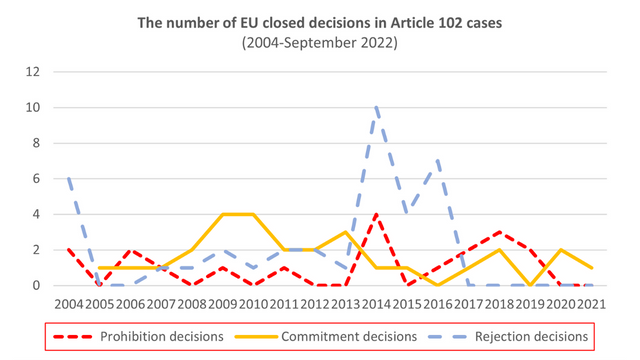

Certainly, the growing number of jurisdictions with the power to accept commitments raises the question of whether in the future we will see the prevalence of commitments over prohibition decisions on a global scale. Concerns about such a trend have, for example, been raised in the academic literature with respect to the evolution of the European Commission’s practice. However, as the graph below shows while the total number of commitment decisions (28) in the period between 2004 and September 2022 exceeds that of prohibition decisions (19), the trend over time does not seem to reveal the existence of a strong bias towards commitment decisions.

Source: Author’s own elaboration of data available on the European Commission’s website.

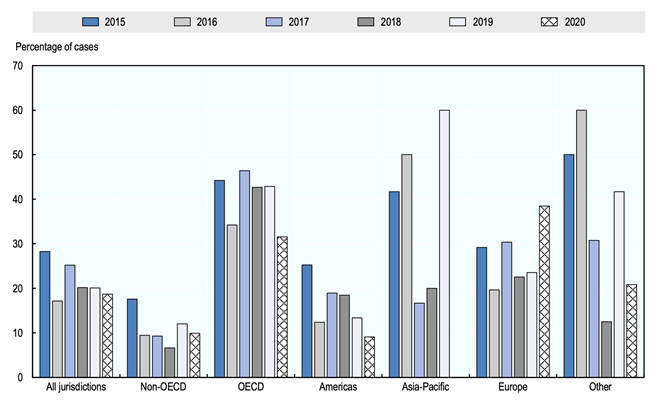

The next graph, which represents the percentage of abuse of dominance cases resolved through settlements or commitment procedure by region, also does not seem to show any discernible common global trend. While in the OECD countries and America this number has slightly decreased in 2020 in comparison to 2018, in the Asia-Pacific region and in Europe it has increased.

Percentage of abuse of dominance cases with settlements or commitment procedures, 2015-2020

Data based on the 56 jurisdictions in the OECD CompStats database that provided comparable data for all six years for both abuse of dominance decisions and abuse of dominance settlements/commitments.

Source: OECD CompStats database

What is interesting about the graph above is what it does not and cannot tell us. First, as many relatively young competition authorities have introduced commitments in their national laws only recently, they might not yet have an experience in this field that could already be reflected in the statistics. For such an experience to be reflected, first, a competition authority must open an abuse of dominance case; second, an investigated firm must spontaneously offer commitments, and third, the proceedings involving the use of commitments must be finalised. All this takes time. It will be therefore interesting to see whether a discernible trend emerges in the next 5 to 10 years when an increasing number of competition authorities will most likely start facing abuse cases in which firms will avail themselves of the newly introduced opportunity to offer commitments. Second, the graph shows the percentage of cases resolved through commitments or settlements per region, which says nothing about what is happening in individual countries, which might follow very different approaches. For example, according to the graph only around 10% of abuse cases in Americas have been resolved through commitments or settlements. However, as discussed during the Forum, in Mexico actually a majority of cases are resolved with the use of such tools.

The challenges ahead

The fact that questions around remedies and commitment continue to be relevant is driven by several factors.

- The process of designing effective and proportionate remedies and monitoring them remains a complex task, even more so in the context of the digital economy where innovation-intensive markets evolve continuously.

- The pervasive presence of dominant firms with global reach raises the question of whether there is a need for more cross-border collaboration on remedies in abuse of dominance cases, and the challenges such collaboration might entail.

- Also, as many abuse of dominance cases occur in regulated markets, improved cooperation between competition and regulatory authorities, and possibly a coordinated design and monitoring of remedies might be both warranted and beneficial.

- The considerations about the optimal use of commitments should take into account not only the overall impact of such tools on the enforcement system and the precedential value of law, but also on the competition authority’s skills, culture and expertise. Resolving most cases through commitments might save scarce resources, but it also deprives competition authorities of developing litigation skills; a concern this particularly relevant for the newly established and less experienced competition authorities.

- Faced with increasingly complex markets, competition authorities shall adopt a comprehensive approach to remedies, intelligently combining structural and behavioural remedies that address competition concerns on both the supply and the demand side. This in turn will require competition authorities to increasingly rely on insights from behavioural economics in an attempt to help consumers overcome their cognitive biases (heuristics).

- While ex-post evaluations in abuse of dominance cases continue to be sporadic, their more frequent use could inform and help design better remedies in the future.

Ultimately, the design of effective remedies and commitments and their monitoring will depend on the ability of competition authorities to deal with the increasing complexities of markets. This in turn raises the question of whether these authorities have adequate resources and expertise to face this challenge. Assessing the technological needs of the authorities and considering whether and how new tools, such as AI, could assist them in the process could be a way forward.