Links

Next content

Read more

The Law and Political Economy Teachings of the AI Act and DMA for the SEP Regulation Proposal

Case Study Through the Better Regulation Framework This paper by Natalia Menendez Gonzalez, Niccolò Galli, and Marco Botta analyses how the EU applied its Better Regulation Framework when drafting the AI Act, the DMA,...

In recent years, the theme of inequality has received attention at the scientific as well as at the policy level, with a growing concern for the impact of the economic and social divide on democratic societies. In parallel, digital innovation not only transformed the economy, society and our daily life, but it also deeply impacted the functioning of democracy and the public sphere. Which is the impact of technological progress on inequality? How should the interplay between traditional and digital inequalities (Helsper 2021) be analysed and understood? In launching its first scientific conference on Digital democracy, the Centre for Digital Society proposes to look at the impact of digital transformation on democracy through the lens of inequality. Our aim is to investigate two main aspects: inequalities in access to and usage of digital technology, and the effects of digitalisation on economic, social, and political inequalities.

A small step back

In 2024, the Centre for Digital Society published a study on the Implications of the Digital Transformation on Different Social Groups. The study, commissioned by the European Parliament, falls in the emerging stream of research on the digital divide, which goes beyond the ability to access information and communication technology, to analyse the socio-economic impact of the digital transformation. In that study, three case studies were proposed, focusing on e-commerce, financial services and access to information. The preparation and discussion of that Study triggered the project to expand and develop the perspective, calling a vast scientific community to analyse and discuss digital inequalities, and to address their impact on the digital public sphere. The vivid debate surrounding the development of Generative AI – both at the scientific and regulatory level – confirms the need for an interdisciplinary approach, bringing together different branches of the scientific community to address what could be a paradigm shift in the human sciences.

Main description

Inequality is a complex phenomenon, which can be defined and measured under different dimensions and characteristics, depending on the answers to the following: Inequality of what? Inequality between whom? While the economic analysis mainly measures and analyses inequalities of income, wealth and consumptions, other dimensions of inequality relate to education, skills, labour market, health, housing, life expectancy, political participation, environment – enlarging the perspective from the inequality of outcome to the inequality of opportunities. All these dimensions can be measured and analysed by social classes (functional income distribution), by gender, by socio-demographic characteristics, by countries, or among individuals.

In recent years, the theme of inequality received a growing attention in the scientific research as well as in the international institutions (OECD 2008, 2011 and 2015; Atkinson 2015; Piketty 2015); the debate focused on the economic dimension of inequality, highlighting widening gaps in income and wealth among individuals within countries – whereas inequality between countries decreased at worldwide level (World Inequality Database; Milanović 2010). Both dynamics occurred in the era of globalisation (Stiglitz 2002; Milanović 2016). “Reduced inequality” is one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations; according to OECD, progress towards this goal, in terms of income and poverty indicators, is very limited, and even when it exists, it is largely insufficient to meet the target. The second and third principles of the European Pillar of Social Rights are, respectively, Gender Equality and Equal Opportunities.

The relationship between technological progress and inequality has been often analysed in the economic theory focusing on the impact of innovation on labour market and wage inequality (Krueger 1993, Acemoglu 2002, Acemoglu & Restrepo 2022). More recently, the development of Generative AI has reignited the debate (Rotman 2022; OECD 2024; Georgieva 2024; The Economist 2025), with a particular focus on the impact of AI on creative and cultural industries (ILO 2025).

Looking at the impact of technological transformation in the overall society, inequality in the digital sphere has been addressed and studied under the category of the digital divide, and originally limited to the technical capability of having or not having access to the internet. In the last two decades, a strong corpus of literature has developed the analysis of other levels of digital inequalities, from individual skills to operational capabilities (Hargittai 2021; Aissaui 2022; for a literature review, see Mazzoni et al. 2024). Applying Amartya Sen’s capability approach to communication, Garnham (1997) points out that “it is not access in a crude sense that is crucial but the distribution of social resources that makes access usable” (p. 27).

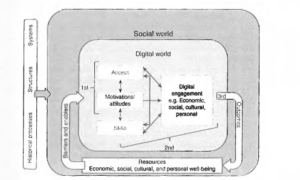

A model of digital inequalities which includes the three levels of digital inequalities (inequalities in access to the internet and infrastructure; inequalities in skills and use; inequalities in the outcome), can be depicted with the following figure:

Source: Helsper (2021), p. 33.

Helsper (2021) conceptualized the need to analysed the interplay between the traditional and the digital inequalities, introducing the term ‘socio-digital inequalities’, defined as “the systematic differences in the ability and opportunity for people to beneficially use (or decide not to use) ICTs, while avoiding negative outcomes of digital engagement now and in the future” (p. 28).

If we understand digital divide in this broader sense, the analysis of digital inequality goes far beyond the (although important) economic and social dimensions, impacting the functioning of the digital public sphere, and the public sphere tout court (Habermas 2022). Digital technology may have a positive impact in terms of reduction of access to markets as well as to electoral competitions; engaging civic participation (see European Parliament’s Re-thinking democracy); connecting areas and social groups which were left behind by physical and technical barriers; reducing the costs of many goods and services reserved in the past to the better offs; as Orly Lobel puts it, digital technology could even work as an “equality machine”, becoming “a powerful force for societal good” (Lobel 2022). On the other hand, digitalisation can widen the gaps between individuals, social groups and countries in terms of skill, education, information, power, and effective capability to access the technological dividend.

Finally, to understand and address the impact of digital transformation on inequalities, the structural characteristics of digital markets and the control of digital infrastructures should be taken into account. The winners-take-all tendency of the digital economy can have nefarious effects on competitive markets as well as on democracy (Zuboff 2019). In this perspective, we also aim to include in our discussion research on the role of the pro-competition tools to restore openness and fairness in the digital markets, as well as on the potential role of an updated competition enforcement (also building on the literature on antitrust and inequalities).

If you are working on any of the (many) topics listed above, and you want to discuss them with a wide community of scholars on the Fiesole’s hills, consider applying – sending your abstract as soon as possible and not beyond June 30th – the text of the Call for paper and all the relevant information are here. The Conference will be held on 20 and 21 November and opened by the keynote speech of Professor Hellen Helsper. Very important final remark: methodological (quantitative and qualitative) and theoretical approaches are both welcome. In particular, refined definitions and empirical approaches to measure digital inequalities, considering institutional, geographical and contextual factors, are warmly welcomed.

References

Acemoglu, D. (2002). Technical Change, Inequality, and the Labor Market. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(1), 7–72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2698593

Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2022). TASKS, AUTOMATION, AND THE RISE IN U.S. WAGE INEQUALITY. Econometrica, 90(5), 1973–2016. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA19815

Aissaoui, N. (2022) The digital divide: a literature review and some directions for future research in light of COVID-19. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 71(8/9) pp. 686-708.

Atkinson, A. B. (2015). Inequality : what can be done? Harvard University Press.

Georgieva, K. (2024). AI will transform the global economy. Let’s make sure it benefits humanity https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2024/01/14/ai-will-transform-the-global-economy-lets-make- sure-it-benefits-humanity

Garnham, N. (1997). Amartya Sen’s “Capabilities” Approach to the Evaluation of Welfare: Its Application to Communications. Javnost-the Public, 4, 25-34.

Habermas, J. (2022). Reflections and Hypotheses on a Further Structural Transformation of the Political Public Sphere. Theory, Culture & Society, 39(4), 145–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632764221112341

Hargittai, E. (Ed.) (2021). Handbook of Digital Inequality. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Helsper, E. J. (2021). The digital disconnect : the social causes and consequences of digital inequalities. Sage Publications.

Krueger, A. (1993). “How Computers Have Changed the Wage Structure: Evidence from Microdata, 1984-1989,” Quart. J. Econ. 110, pp. 33-60.

ILO (2025). Generative AI and the media and culture industry. Research brief.

https://www.ilo.org/publications/generative-ai-and-media-and-culture-industry